Seventy years ago the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education changed the trajectory of public education and sparked the end of segregated schools.

Before the Brown decision was handed down in 1954, there was Plessy v. Ferguson. In 1892 Homer Plessy, a Black man of New Orleans, Louisiana, volunteered to test the legality of railroad car segregation in that state. He sat in a “whites only” car, refused to move to a segregated car, was arrested, and sued in court. When Plessy was arrested, he contested that Louisiana’s law violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The case eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in 1896 that segregation was legal as long as the accommodations were “separate but equal.”

The 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision further reinforced the rise of segregation. The Court rendered this decision despite the reality that separate areas provided for African Americans rarely were equal. John Marshall Harlan, the only dissenting justice, argued against the decision: “The arbitrary separation of citizens, on the basis of race … is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution.”

Despite the refusal of the courts or politicians to support them, African Americans continued to challenge segregation and demand their equal rights under the Constitution. They pressed forward their fight in the belief that their efforts might eventually result in change.

In 1952, five different cases from across the nation came before the high court. They would all be condensed under Brown v. The Topeka Board of Education explained Tona Boyd, associate director-counsel for the Legal Defense Fund.

“Oliver Brown was the father of Linda Brown, who was at the time trying to attend third grade in a school that was just around the corner from her. But because the school was all white, she was rejected,” Boyd said.

Thurgood Marshall, who would later become a justice on the high court, led a group of esteemed lawyers — Robert Carter, Jack Greenberg, Constance Baker Motley, Spottswood Robinson, Oliver Hill, Louis Redding, Charles and John Scott, Harold R. Boulware, James Nabrit, and George E.C. Hayes — in arguing the case before the court.

And when they won, Boyd said, it opened the door for changes across the country. “Brown was a case that was brought to challenge that malignant doctrine that had been endorsed by the court and allowed state sanctioned segregation to be permitted in almost all areas of American life, from public schools to trains, cars, to places of public accommodation,” she said.

“Though segregation is illegal, our schools still remain segregated today,” Jalisa Evans, chief executive officer and founder of The Black Educator Advocates Network, told The Hill. “As white students fled school districts to avoid integration, redlining continued to create segregated schools through housing. Today, schools with large numbers of Black students are underfunded.”

In December 2022, the Education Trust found that districts with predominantly non-white students receive more than $2,000 less per student than predominantly white districts. In a district with 5,000 students, that would equate to $13.5 million in missing resources.

Advocates also point to recent Supreme Court decisions they say disrupt the 1954 decision. Now, 70 years after the landmark ruling, leading Black voices are concerned that the ruling is slowly being chipped away.

“While we celebrate 70 years of the first Supreme Court decision to break down Jim Crow in education — and the implications were beyond education — that celebration is dampened by the fact that we now have a Supreme Court that has taken out affirmative action and attacked voting rights,” the Rev. Al Sharpton told The Hill. “If this Supreme Court was sitting in 1954, they probably would have not voted for Brown versus the Board of Education,” he added.

“We’ve come a long way since the Supreme Court ruled that school segregation was unconstitutional,” House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) said in a statement. “But today, the most segregated school systems in America can be directly traced to policies put in place in the aftermath of Brown v. Board of Education.”

“Today, we carry the torch by fighting for that history to remain in our nation’s classrooms. The effort to establish equitable access to education continues to be an uphill battle for Black Americans as we witness modern-day attacks on educational rights, such as the erasure of Black history in schools and elimination of affirmative action in higher education,” Derrick Johnson, President and CEO, NAACP shared.

“As we mark the 70th anniversary of the Brown v Board becoming law, we honor the courageous individuals who have fought tirelessly for racial equity and justice in our country’s educational system — long before this landmark ruling, and long after it, too. Brown v. Board was a pivotal moment in our nation’s history, not only striking down the doctrine of ‘separate but equal,’ but also catalyzing a movement towards equality and inclusion in our schools,” Congressman and Former Principal Jamaal Bowman. “But, as we reflect on this milestone, we must also recognize that this critical work is ongoing. We must continue working to dismantle the systemic barriers that still hinder educational opportunities for far too many children: here in New York, and across the country. Let us honor this anniversary and the work of all those who came before us with action, and recommit ourselves to the pursuit of a truly equitable education system, where every child has the opportunity to thrive and succeed.”

The Desegregation of Yonkers

Here is Westchester County, there was a school and housing desegregation case in Yonkers. The initial complaint was filed by the U.S. Department of Justice in 1980, and the Yonkers branch of the NAACP intervened in 1981 to make the case a class action. After 27 years, the parties settled in 2007, with Yonkers agreeing to build 800 units of public housing in predominantly-white East and Northwest Yonkers. This case was highly contentious: in the late 1980s, Yonkers defied the court’s desegregation orders, resulting in contempt fines that reached $1 million per day and brought Yonkers to the brink of bankruptcy. HBO dramatized this conflict in the 2015 series Show Me a Hero.

In 1980, the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division brought this case in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York against the City of Yonkers, New York, alleging that the City had intentionally segregated its schools by deliberately concentrating public housing in Southwest Yonkers. Specifically, the complaint was brought to enforce Titles IV and VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and it alleged violations of Title VIII of the Fair Housing Act, the 14th Amendment, Department of Education regulations, and contractual assertions made by Yonkers to access federal educational funds. By preventing public housing from being built in majority-white neighborhoods, Yonkers officials had ensured that Yonkers schools were almost entirely segregated by race. According to the opinion available at 518 F. Supp. 181, the complaint also alleged that the City and the school board enabled segregation through racially discriminatory policies and through the repeated appointment of school board members who opposed integrating Yonkers schools. The complaint aimed to desegregate Yonkers schools by desegregating Yonkers housing – specifically, by requiring Yonkers to build public housing in majority-white neighborhoods.

The Yonkers branch of the NAACP intervened in 1981, on behalf of a child in the Yonkers public school system. Thereafter, the school desegregation aspect of the case was certified as a class action, with the class defined as all black or Hispanic children attending a Yonkers public school. The housing desegregation aspect of the case was also certified as a class action, the class defined as any Yonkers resident eligible for or living in public housing in Yonkers. 518 F. Supp. 191.

Because of the divisiveness of the litigation and its potential cost, Judge Leonard B. Sand appointed a Special Master in September 1982 to help the parties negotiate a settlement to both the housing and schooling prongs of the case.

This case occurred in parallel with a case to desegregate the Yonkers Police Department. For more information about that case, see United States v. City of Yonkers, 609 F. Supp. 1281 (1984).

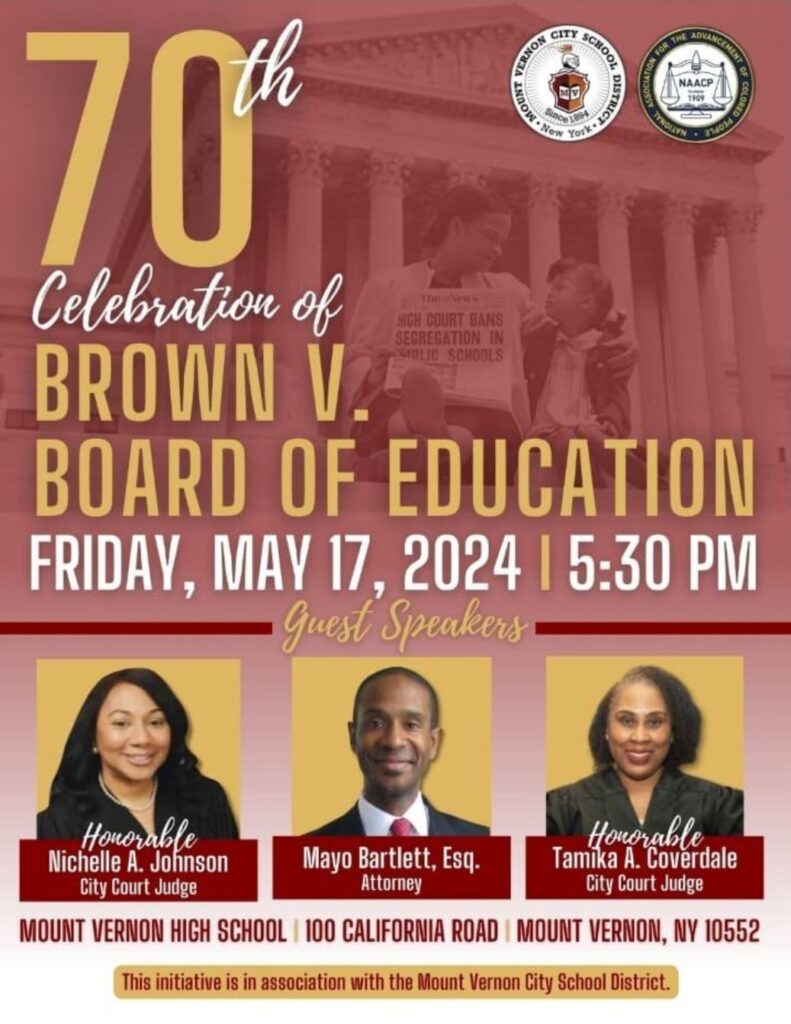

Mount Vernon NAACP & City School District Celebrate 70 Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Ed

The Mount Vernon City School District and the Mount Vernon branch of the NAACP celebrated the 70th Anniversary of the landmark decision that made school segregation illegal in America, at Mount Vernon High School (100 California Rd.), Friday, May 17, 2024. Panelists included Civil Rights Attorney Mayo Bartlett who discussed the Brown case and its impact, Mount Vernon City Court Judge Nichelle Johnson who discussed the history and what was happening before Brown and Mount Vernon City Court Judge Tamika A. Coverdale who discussed the important of women around Brown.

Civil Rights attorney Mayo Bartlett said there is not enough honest conversation about why it has been hard to desegregate schools. At a recent panel he discussed the generational wealth gap between Black and white people, which often leads them to live in different places. He shared that Black families being systematically steered to buy homes in certain neighborhoods away from white families.

“More affluent schools will have more resources. Poorer schools will have fewer resources. That means it’s never going to be separate but equal. It’s always going to be separate, and the haves will have more and the have-nots will have less,” he shared with Black Westchester after panel discussion.

Panelists and attendees at the Mount Vernon High School event reflected on how many school districts are failing to integrate 70 years since the Brown v. Board of Education decision. You can view video of the panel discussion on the Mount Vernon NAACP Facebook page.

[…] Source link […]